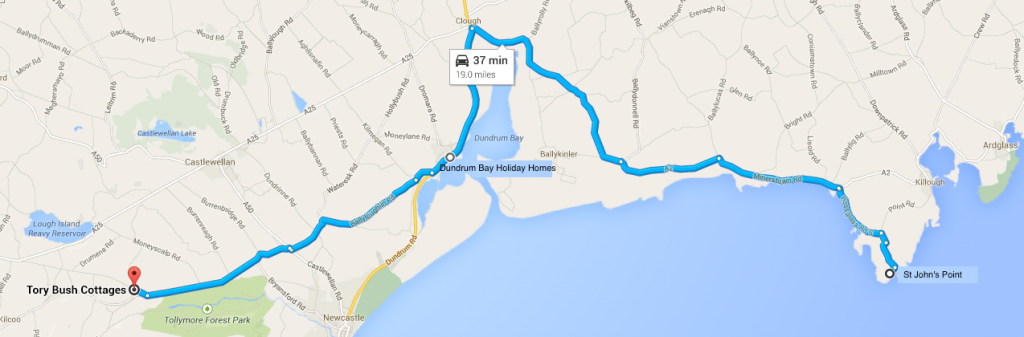

The area around Tory Bush is full of hidden gems. One of my favourites is St John’s Point near Killough, Co Down and about half an hours drive from Tory Bush and featured in a recent Radio 4 Open Country programme.

St John’s is not just the site of a lighthouse but also the site of one of the earliest Christian Churches in the North of Ireland. More about the Church in a later Blog, the Lighthouse is now to be part of a ‘Lighthouse Trail’ linking about 8 Lighthouses in interesting sites around the coast of Ireland, here at St John’s the plan is to build two visitor self-catering accommodation units in the old Lighthouse Keepers Cottages and to improve Visitor access facilities, at the present the site is a bit impregnable behind a high wall.

The lighthouse at St John’s is famous or infamous for a number of reasons, it has been recently suggested that the Captain of Brunel’s famous SS Great Britain, the world’s first ironclad ship on setting out on it’s 3rd transatlantic crossing made a navigational error mainly due to not having updated charts, he mistook the new St John’s lighthouse on the County Down Coast for the Calf light on the Isle of Man and ran the ship aground on the inner Dundrum Bay, where she spent the winter of 1846 for more details check out the Tory Bush Facebook page This is not the only occasion when the lighthouse was mistaken for another lighthouse, in 1855 a ship, ‘The Fortune” bound for Australia sailing out of Liverpool again ran aground in Dundrum Bay when the Captain one James McCarthy mistakenly, ” thought that the Kish light was St.John’s Point light, and he mistook St.John’s Point light,for the Copeland lights.”. The ship ran aground near Tyrella and one passenger lost his life whilst abandoning ship and the subsequent Enquiry and Coroners Inquest as reported at the time make interesting reading. Until the building of the Lighthouse and even for a time after there were cases where ‘ vessels are driven on shore, after a deliberate plan to wreck them, and make money more easily by defrauding the underwriters than by risking the perils of long voyages'”. The Captain in this case was cleared of all malice afore-thought.

St John’s enters another league of infamy with it’s association with the famous Irish playwright Brendan Behan, Behan was the son of a House Painter and one of their contracts was the painting of the Lighthouses around Ireland, I am not sure if the colours were yellow and black then as apparently St John’s was used as an experiment to trial this colour scheme to see if it stood out in foggy and hazy days, the experiment must not have been classed as a success as no other Lighthouses followed suit. In the summer of 1950 Brendan was sent up to paint the Co Down lighthouse but his efforts were less than diligent as this letter from the Light Keeper at the time makes clear.

Below is a copy of an excellent article by Ciara Colhoun featured a few years ago in the local paper the Down Recorder.

A summer in Co. Down with Behan

By Ciara Colhoun

ONE of Ireland’s most irreverent writers caused havoc when he was employed to paint St. John’s Point lighthouse over 60 years ago, according to documents recently unearthed.

Retired local lighthouse keeper Henry Henvey has personally recalled the irritation Brendan Behan caused his former employer when he arrived at St. John’s Point in the summer of 1950.

Mr. Henvey, who was a teenager at the time, befriended the budding playwright and has pleasant memories of swimming together in the open sea and enjoying long conversations in the family kitchen.

He recalls Behan spending a lot of time with a neighbour, Miss. Montgomery, who was regarded locally as an intellectual, and says he was later delighted to receive postcards from Behan when he moved to Paris, urging Henry to consider relocating due to the opportunities available in the French capital.

But Henry’s positive experience is at odds with that of the principal lighthouse keeper at the time, Mr. D. Blakely, who was so horrified by Behan’s behaviour that he penned a letter to his boss, calling for his immediate dismissal.

Mr. Henvey keeps a copy of this letter, alongside other documents relating to Behan’s employment, in historical files belonging to the lighthouse.

In it, Mr. Blakely describes Behan as “the worst specimen” he has met in 30 years of service and accuses him of showing “careless indifference” and no respect for property.

He said Behan, who had been released from borstal just four years previously for being a member of the IRA, had failed to turn up for work one day, not returning to the station until 1.25am.

“He is wilfully wasting materials, opening drums and paint tins by blows from a heavy hammer, spilling the contents which is now running out of the paint stores.

“Drums of waterwash opening and exposed to the weather, paint brushes dirty and lying all around the station — no cleaning up of any mess but he tramps through everything.

“His language is filthy and he is not amenable to any law or order.

“The spare house, which was clean and ready for painters has been turned into a filthy shambles inside a week.

“Empty stinking milk bottles, articles of food, coal, ashes and other debris litter the floor of the place which is now in a scandalous condition of dirt.”

Mr. Blakely ends his letter with an urgent call for Behan’s dismissal “before the place is ruined.”

Despite this call, however, Mr. Henvey says Behan was retained by the Irish Lights Office, who held Behan in high regard.

Rather than being dismissed, Behan was retained for a second summer stint as a lighthouse painter, before moving to Paris where he settled into his career as a writer.

Although he kept in touch with Mr. Henvey by postcard, the two men never met again as Mr. Henvey was working at sea when Behan returned to visit the area. However, he says he keenly followed his career, enjoying each piece of Behan’s work as it was published.

“Even as a school boy I was very impressed by Behan, who was already writing s for plays at that time,” he said.

“He told me all about being in jail in Liverpool and said the warden had picked him out from a line-up of boys as an intellectual.

“He saw that he was different from the rest and gave him books to study to try to keep him on the straight and narrow.

“Every Christmas Eve, even after he returned to Dublin, the warden phoned him to see how he was doing.

“Behan kept in touch in Paris but when he moved onto New York I never heard from him again. Like many a good man, he succumbed to beer.”(A little side note, earlier this year I came across this review of Brendan Behans last years in New York, – The Rise and Fall of the most Famous Irish Man in New York”

Mr. Henvey said he had been asked to lend the letter about Behan to a man to photocopy years ago and was disappointed that the original letter was not returned to him. He said the postcards Behan had written to him were now in England.

Just four years after his unsuccessful stint as a lighthouse painter, Behan sealed his place as one of Ireland’s best known writers and talkers with the production of his first highly acclaimed play “The Quare Fellow’. Four years later again, he made use of the irreverence that so troubled his lighthouse employers to create his best-selling autobiographical book, ‘The Borstal Boy”, which told the story about his own time spent in prison.

Now one might imagine that was the end of the incidents involving painters at St John’s Point but in March this year year a painter was trapped halfway up the lighthouse when his platform fell away from the building and he had to be rescued by a specialist team from the Fire and Rescue Service.

Further to my original post which ended at the previous sentence I sent a copy of the post to the Commissioners of Irish Lights and got a very nice reply with a link to a page with the history of the Lighthouse at St John’s its height etc.. St John’s was originally 18.9 metres giving a range of 12 mile across the water, but in the 1890’s it was increased to 40 metres giving a range of 25 mile out over the water. This is as about as high as it needed to be as the horizon is approximately 27 miles away before the earth curves and so the height any lighthouse must take in to consideration the curve of the earth and the height of the ground that the lighthouse is standing on. But the light should not be so high up that local sailors will not see it. It is possible that a sailor sitting a mile or so out at sea may not see the light if the beam is too high. Hence, you will frequently get shorter lighthouses on the top of cliffs and taller lighthouses built nearer the water surface.

The page also gave an insight into the present colour scheme of the lighthouse, when originally built in 1844 it was painted all white, and even when increased in height it was still all white, however in 1902 three black bands were added and then in 1954 the colour was changed to the present scheme which is really a Black Tower with two Yellow bands. Based on this it can be safely assumed that when Brendan Behan was painting the Lighthouse in 1950 that it was still the older Black and White paint scheme, – before the advent of modern polyurethane paints which last 8-10 years, the paint used in the middle of the last century lasted about 4-5 years which fits with the change to Yellow and Black in 1954.